On Nov. 24, 1954, Radio Peking (in mainland China) announced that eleven US airmen, as well as two other Americans, both of whom were described as special agents of the CIA, had been convicted of espionage by a military tribunal in China and sentenced to prison terms from four years to life. The eleven US airmen, serving under the United Nation’s Unified Command in Korea, were crew members of a B-29 which had been shot down on January 12, 1953, while conducting leaflet-dropping operations over North Korea. The question before the US government was how to secure the release of the airmen imprisoned in China as Washington did not recognize ‘mainland China’ as a country and so did not have any diplomatic ties to Peking. “When in December 1954 the US – after trying many other approaches in vain – brought this question to the Ninth session of the United Nation’s General Assembly, the UN was faced with an apparently insoluble problem. It seemed unlikely, to say the least, that an organization that had excluded and rejected the government of the largest nation on earth would have much success in prevailing on that government to release hostile airmen who had landed in China and had already been convicted as spies.”(1)

On December 6 the permanent US representative to the UN, Henry Cabot Lodge, informed the United Nations Secretary-General, Dag Hammarskjold, that Washington would like him to be personally involved in negotiating the release of the US airmen “since it was believed that he was more likely to get results than anyone else”…(2)

Hammarskjold had an all-night discussion with a trusted Swedish colleague, Sture Petren, before he made up his mind to accept the assignment if he was requested by the General Assembly to undertake a mission of this kind. He also decided that he would personally travel to Peking and approach the Chinese premier Chou En-lie directly. In doing this Hammarskjold was taking a very big diplomatic risk and putting himself in a very delicate position. As Lodge put it six months later, in offering to go to Peking Hammarskjold “put his life’s reputation as a diplomat on the chopping block”.(3) But Hammarskjold had come to the conclusion that only a bold move had any chance of success. “In the days just before passage of the General Assembly resolution on December 10th, he met with senior diplomats privately and saw to it that the resolution included language that gave him considerable latitude. Those key words authorized the secretary-general to undertake the mission “by the means most appropriate in his judgment””.(4)

On December 10 after receiving the formal request from the General Assembly of the UN ‘to seek the release of the eleven UN Command personnel captured by Chinese forces on 12 Jan 1953 as well as of all other captured personnel of the United Nations Command still detained’ Hammarskjold sent a message to Chou En-lai informing him of the General Assembly resolution and also stating that “In the light of the concern I feel about the issue, I would appreciate an opportunity to take this matter up with you personally. For that reason I would ask you whether you could receive me in Peking”…(5)

On Dec. 17 Chou En-lai replied, “in the interest of peace and relaxation of international tension, I am prepared to receive you in our Capital, Peking, to discuss with you pertinent questions”.

(At this point in our story it is worth taking a slight detour to take note of two very interesting observations Roger makes during this period in Hammarskjold’s life:

No doubt late in the evening of December 10th, when so much had already occurred, he found his way to the Book of Common Prayer and transcribed (into his journal) the concluding lines of Psalm 62, giving his own emphasis to words by which he must have felt especially addressed:

“God spake once, and twice I have also heard the same: that power belongeth unto God;

and that thou, Lord, art merciful: for thou rewardest every man according to his work.”(6)

At some point on the day of departure, December 30th, he took time to record in his journal, from Psalms, an expression of faith that could reach around the world:

“If I take the wings of the morning and remain in the uttermost parts of the sea; even there also shall thy hand lead me.”(7) )

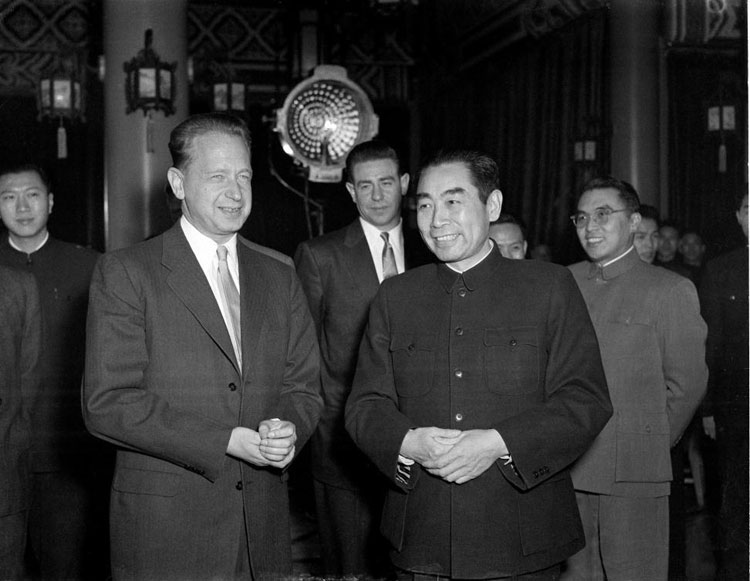

Along with his small team of experts Hammarskjold arrived in Peking on January 5, 1955. Between Jan. 6 and Jan. 10 four meetings were held. (In the midst of these talks Hammarskjold and his team also found time to go sight-seeing.) “From the very first Chou En-lai and Hammarskjold seem to have made a good impression on each other, and their mutual respect and understanding was an important factor in the subsequent talks.”(8) “Each was a mandarin of his culture. Prompted by ideals and a love of humanity that counted for more than mandarin fastidiousness, each had dived into the world of action. Henry Kissinger’s description of Chou many years after the Hammarskjold-Chou encounter could be of Hammarskjold: ”equally at home in philosophy, reminiscence, historical analysis, tactical probes, humorous repartee…[he] could display an extraordinary personal graciousness…One of the two or three most impressive men I have met””.(9)

By the end of the talks Chou and Hammarskjold did not see eye to eye on any point. They could not agree on any of the facts and their legal interpretations. Despite these disagreements Hammarskjold suggested that “there remained an option: in the interest of relaxing international tensions, to “trust that [China] will reach its final conclusion in a spirit of justice and fairness – before [its] own conscience”. At that level Chou could respond. Chou offered some assurance that a formula focused strictly on relaxing tensions might lead to early release, other conditions permitting. It was not a guarantee and said nothing about timing, but his assurance was crucially important to Hammarskjold”.(10)

On his return to New York on January 13, Hammarskjold was publicly saying that there must be “restraint on all sides” emphasizing that “the door was open and could remain open with due restraint”. But alas on January 17, US Senator Knowland attacked the mission as “a failure by any standard or yardstick”…Of the US attitudes that were now the central factor in achieving the release of the airmen, Hammarskjold wrote on January 25 to (Humphrey) Waldock, “I am afraid that their emotions have run away with their political wisdom”.(11)

On January 31 writing to a friend, the director of Swedish Royal Library, Uno Willers, about his recent experiences in Peking and with Washington Hammarskjold stated, “The mission to Peking was not only unique in diplomatic history but also unique as a human experience…The contacts with Chou En-lai and with this whole very foreign world made an enormous impression on me, and I would wish that other policy makers had got it…It is a little bit humiliating when I have to say that Chou En-lai to me appears as the most superior brain I have so far met in the field of foreign politics… As I said to one of the Americans: “Chou is so much more dangerous than you imagine because he is so much better a man than you have ever admitted.”(12)

(During this period Roger observes very insightfully “After Peking he returned to his fundamental truths. “Before Thee in humility, with Thee in faith, in Thee in stillness”, he wrote at this time in his journal, each element both a truth of his inner world and a gesture, an act of alignment.”(13) Hammarskjold must have made this entry in his journal sometime between January and March of 1955.)

In the months that followed after Hammarskjold’s return from Peking situations evolved in a way that made it extremely difficult for him to obtain the release of the eleven airmen. Sometime in mid-June Hammarskjold felt the possibility of failure more keenly than at any other time. “Difficulties,” he wrote to Lodge, “have piled up in a way entirely outside the control of the United Nations.”(14) In spite of delays and difficulties, Hammarskjold and Chou kept in touch with each other through private channels.

Sometime in early July, Chou through his charge d’affaires in Stockholm wanted to know what kind of gift Hammarskjold would like for his 50th birthday (which was on July 29th.). The reply was ‘the release of the eleven American prisoners would be by far the best gift’.

On August 1st Hammarskjold, who was holidaying at that time in south Sweden, received a cable from Peking informing him of the release of the imprisoned US airmen and it was clearly stated in the cable that “This release (of the US airmen) from serving their full term takes place in order to maintain friendship with Hammarskjold and has no connection with the UN resolution. Chou En-lai expresses the hope that Hammarskjold will take note of this point…Chou En-lai congratulates Hammarskjold on his 50th birthday.”(15)

On the successful conclusion of the Peking affair, Urquhart writes, “The success of his (Hammarskjold’s) mission established him once and for all as a major resource of the international community for dealing with difficult problems and as an important international figure in his own right…After August 1955 his style changed noticeably, as if, at the completion of the affair of the American prisoners in China on his fiftieth birthday, he had come of age as Secretary-General.”(16) The Peking affair also showed the member states of the United Nations that their Secretary-General was “an international negotiator of exceptional resource, daring, and competence, with the capacity to get positive results even out of the most apparently hopeless situations”.(17)

References:

1) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 96

2) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 99

3) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 102

4) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 211

5) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 101

6) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 214

7) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 219

8) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 105

9) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 217

10) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 220

11) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 114

12) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 117

13) Hammarskjold A Life, Roger Lipsey, University of Michigan 2013, Pg. 227

14) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 125

15) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 126

16) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 131

17) HAMMARSKJOLD, Brian Urquhart, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1972, Pg. 96

Comments are closed.