The Loss

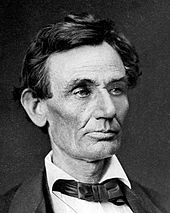

In 1858 Abraham Lincoln accepted the Republican Party’s nomination to run for the Illinois Senate seat against the Democratic incumbent Stephen Douglas. (In those days, U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures; so the candidate whose party won control of the state legislature was elected.) Despite the Republican Party winning the popular vote, Lincoln lost the election because the Republicans did not gain control of the Illinois state legislature. (In the election the Republicans received about 50 percent of the popular vote and won only 47 percent of the seats in the house. Where as the Democrats received 48 percent of the popular vote and won 53 percent of the seats. On January 5, 1859, when the balloting took place in the Illinois state legislature Douglas received 54 votes to Lincoln’s 46 and was thus reelected for another six years to the United States Senate.) But this defeat proved to be the stepping stone for Lincoln to win the Republican presidential nomination and ultimately the presidency. Lincoln who was little known outside his home state gained national recognition after his splendid performance in the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates.

In 1858 Abraham Lincoln accepted the Republican Party’s nomination to run for the Illinois Senate seat against the Democratic incumbent Stephen Douglas. (In those days, U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures; so the candidate whose party won control of the state legislature was elected.) Despite the Republican Party winning the popular vote, Lincoln lost the election because the Republicans did not gain control of the Illinois state legislature. (In the election the Republicans received about 50 percent of the popular vote and won only 47 percent of the seats in the house. Where as the Democrats received 48 percent of the popular vote and won 53 percent of the seats. On January 5, 1859, when the balloting took place in the Illinois state legislature Douglas received 54 votes to Lincoln’s 46 and was thus reelected for another six years to the United States Senate.) But this defeat proved to be the stepping stone for Lincoln to win the Republican presidential nomination and ultimately the presidency. Lincoln who was little known outside his home state gained national recognition after his splendid performance in the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates

The central issue during the Lincoln-Douglas debates was slavery, especially the issue of slavery’s expansion into the territories.(Territories of the United States were political division of the U.S., overseen directly by the federal government of the United States but were not any part of a U.S. state. These territories were created to govern newly acquired land while the borders of the United States were still evolving.) Lincoln was against the expansion of slavery into the territories where as Douglas was advocating the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which meant that, people of a territory could decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. Lincoln was against popular sovereignty and the extension of slavery that it would allow.

Comparing Lincoln and Douglas journalist Henry Villard, who attended the first debate, said that Douglas had a strong, sonorous voice and was a gifted speaker. Lincoln on the other hand did not have any such advantages. Lincoln had a lean, lank, gawky figure with an uncomely face and his body gestures when he spoke were very awkward. Reflecting on this debate Villard added that even though Douglas was a skillful dialectician and debater, he was arguing a wrong and weak cause whereas Lincoln came off as a “thoroughly earnest and truthful man, inspired by sound convictions in consonance with the true spirit of American institutions.” Villard also said, “There was nothing in all Douglas’s powerful effort that appealed to the higher instincts of human nature, while Lincoln always touched sympathetic chords. Lincoln’s speech excited and sustained the enthusiasm of his audience to the end.”1

Ohio journalist David Locke recalled that Douglas was the demagogue all the way through. He suppressed facts, twisted conclusions, and perverted history. In short Douglas was laboring for himself and nothing else. Of Lincoln, Locke said, “the cause for which he was speaking was the only thing he had at heart; that his personal interests did not weigh a particle. He was the representative of an idea, and in the vastness of the idea its advocate was completely swallowed up…His great strength was in his trusting the people instead of considering them as babes in arms. He did not profess to know everything. The audience admired Douglas, but they respected his simple-minded opponent.”2 According to scholars of those times, Mr. Lincoln was the deeper thinker – more grounded in philosophy and ideas.

Throughout the campaign, Senator Douglas rode in a special train provided by the Illinois Central Railroad while Lincoln traveled in near poverty. He generally traveled on regular trains and if he failed to get one was forced to travel on freight trains.

This Senate contest between Lincoln and Douglas evoked both local and national interest. A report on this campaign by the New York Evening Post stated, “It is astonishing how deep an interest in politics this people take. Over long dreary miles of hot and dusty prairie, the processions of eager partisans come – on foot, on horseback, in wagons drawn by horses or mules; men, women and children, old and young, the half sick just out of the last ‘shake’; children in arms, infants at the maternal front, pushing on in clouds of dust and beneath a blazing sun; settling down at the town where the meeting is, with hardly a chance for sitting, and even less opportunity for eating, waiting in anxious groups for hours at the places of speaking,..”3

The Triumph

Preparation for the Presidency

During the 1958 senatorial campaign against Douglas, Lincoln told journalist Henry Villard that he doubted his ability, to be a senator, though his wife was confident that he would one day become President. “Just think” he exclaimed, wrapping his long arms around his knees and giving a roar of laughter, “of such a sucker as me as President.”7 Lincoln was perfectly aware of the realities – he did not have any family tradition or wealth, he had received very little formal schooling, he had no administrative experience of any kind and for the past ten years had held no public office except for one term in the House of Representatives.

In spite of these disadvantages Lincoln could not help thinking of the Presidency. When he analyzed his own chances against the better known rivals he realized that his chances for securing the Republican nomination seemed better than average. There were several strong candidates in the Republican Party but all had flaws. Among the potential candidates senator William H. Seward of New York was the leading name. He was able, experienced and well connected. But because he proclaimed a higher law than the Constitution and predicted an irrepressible conflict between slavery and freedom, was considered an extremist. The Republican governor of Ohio, Salmon P. Chase, sought the nomination but he was neither charismatic nor a skilled politician. Simon Cameron from Pennsylvania had few followers outside his state and was suspected of being highly corrupt. Then there was Missouri’s Edward Bates who was known only in his state.

Instead of announcing his candidacy Lincoln started making small, quiet moves to consolidate his strength and increase his influence.

He compiled the 1858 debates between him and Douglas and got it published by Follett, Foster & Company of Columbus Ohio as a 268 – page book titled ‘Political Debates between Hon. Abraham Lincoln and Hon. Stephen A. Douglas in the Celebrated Campaign of 1858, in Illinois’. The book was released shortly before the national nominating conventions of 1860. It instantly became a best-seller.

Cooper Union Address

In mid-October 1859 Lincoln accepted an invitation to lecture at Henry Ward Beecher’s church in Brooklyn, New York. Realizing that this speech in the East (in Seward’s home state) could put him in consideration for the Republican presidential nomination, Lincoln requested the speech be moved from November to late February, closer to the party convention. Then Lincoln spent the next four months researching and preparing the speech. About this speech his law partner William Herndon said, “No former effort in the line of speech-making had cost Lincoln so much time and thought as this one…” According to Herndon the speech was “devoid of all rhetorical imagery.” Rather, “it was constructed with a view to accuracy of statement, simplicity of language, and unity of thought. In some respects like a lawyer’s brief, it was logical, temperate in tone, powerful – irresistibly driving conviction home to men’s reasons and their souls.”

At the last minute the venue for the address was changed from Beecher’s church to the Great Hall at Cooper Union. On the night of February 27, 1860 Lincoln addressed a crowd of 1,500 New Yorkers. He delivered the speech by reading carefully from sheets of blue foolscap. It was the longest speech Lincoln ever gave. He spoke for over an hour. He ended his speech by saying, “Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

Lincoln’s speech was a grand success. It electrified his audience and when he finished they cheered and stood, waving handkerchiefs and hats. Noah Brooks the journalist for the New York Tribune, exclaimed: “He’s the greatest man since St. Paul.” The next day most of the New York papers printed the address in full. The favorable publicity Lincoln’s speech received was absolutely breathtaking. This was indeed a brilliant political move for an unannounced presidential candidate. Lincoln was invited to speak in several other cities in the east (New England) before returning to Illinois. Holzer writes, “It is fair to say that never before or since in American history has a single speech so dramatically catapulted a candidate toward the White House”4.

Winning the nomination and the Presidency

After returning from New York, Lincoln conferred with few of his close associates about his nomination and then finally authorized the group to work for his nomination. To his friend senator Lyman Trumbull, Lincoln said, “The taste is in my mouth a little.”5

On May 9-10 1860, one week before the Republican national convention, the Illinois Republican State convention in Decatur passed a resolution that “Abraham Lincoln is the choice of the Republican party in Illinois for the presidency”. During the national convention held in Chicago, Lincoln remained in Springfield closely monitoring the convention proceedings via telegrams he was receiving from Chicago. During the voting in the first ballot Seward got 173 ½ votes, Lincoln 102; Bates 48; Cameron 50 ½; Chase 49. A total of 233 votes were needed to win the nomination. In the second ballot Seward had 184 ½ votes and Lincoln rose to 181 votes. In the third ballot Seward’s votes remained steady but Lincoln’s increased to 231 ½, one and a half votes short of a majority. At that point four Ohio delegates switched from Chase to Lincoln followed by many other delegates giving Lincoln a total of 364, out of a possible 466 votes. Then Seward’s men moved to make the nomination of Lincoln unanimous. During the convention Lincoln’s men headed by Judge David Davis cleverly out-maneuvered Seward’s men at every stage and engineered a brilliant nomination victory for Lincoln.

In the mean time the Democratic party split into the Northern and Southern factions. The Northern Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois for president and the Southern Democrats nominated John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky as their presidential candidate. Because of the split in the Democratic party, Lincoln’s victory in the Presidential election was almost assured.

The Presidential election was held on November 6, 1860 and Lincoln received 1,866,452 votes to 1,376,957 for Douglas and 849,781 for Breckinridge. Lincoln won 180 votes in the Electoral College to 72 for Breckinridge and 12 for Douglas. Lincoln won the Presidency.

Thus it was for Lincoln. In almost every situation in life Lincoln started off as a looser only to emerge triumphant. By mid 1861 things were going so badly for Lincoln as President that everyone thought the President was honest and well meaning but incompetent. Yet in the end Lincoln went on to become one of the most successful and one of the most loved of American Presidents. During his presidency Lincoln often joked “my policy is to have no policy”6. For all his outer flexibility, Lincoln’s actions and decisions were based on certain underlying principles – his uncompromising adherence to truth, his unalloyed love for the country and his deeply humane and sympathetic heart. It is Lincoln’s noble character and noble deeds that have made him a household name in almost every corner of the globe.

References

1. Life on the Circuit with Lincoln, Henry Clay Whitney, p. 402 2. The Radical and The Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antisalvery Politics, James Oakes, pp. xiv. 3. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: A Case Study in ‘Stump Speaking’, Richard Allen Heckman, p. 55. 4.Lincolnat Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President, Harold Holzer, p. 235. 5. Lincoln, David H. Donald, p. 241. 6. Lincoln, David H. Donald, p. 332. 7. Lincoln, David H. Donald, p. 235. Mallikarjun Nov 18, 2011

Comments are closed.